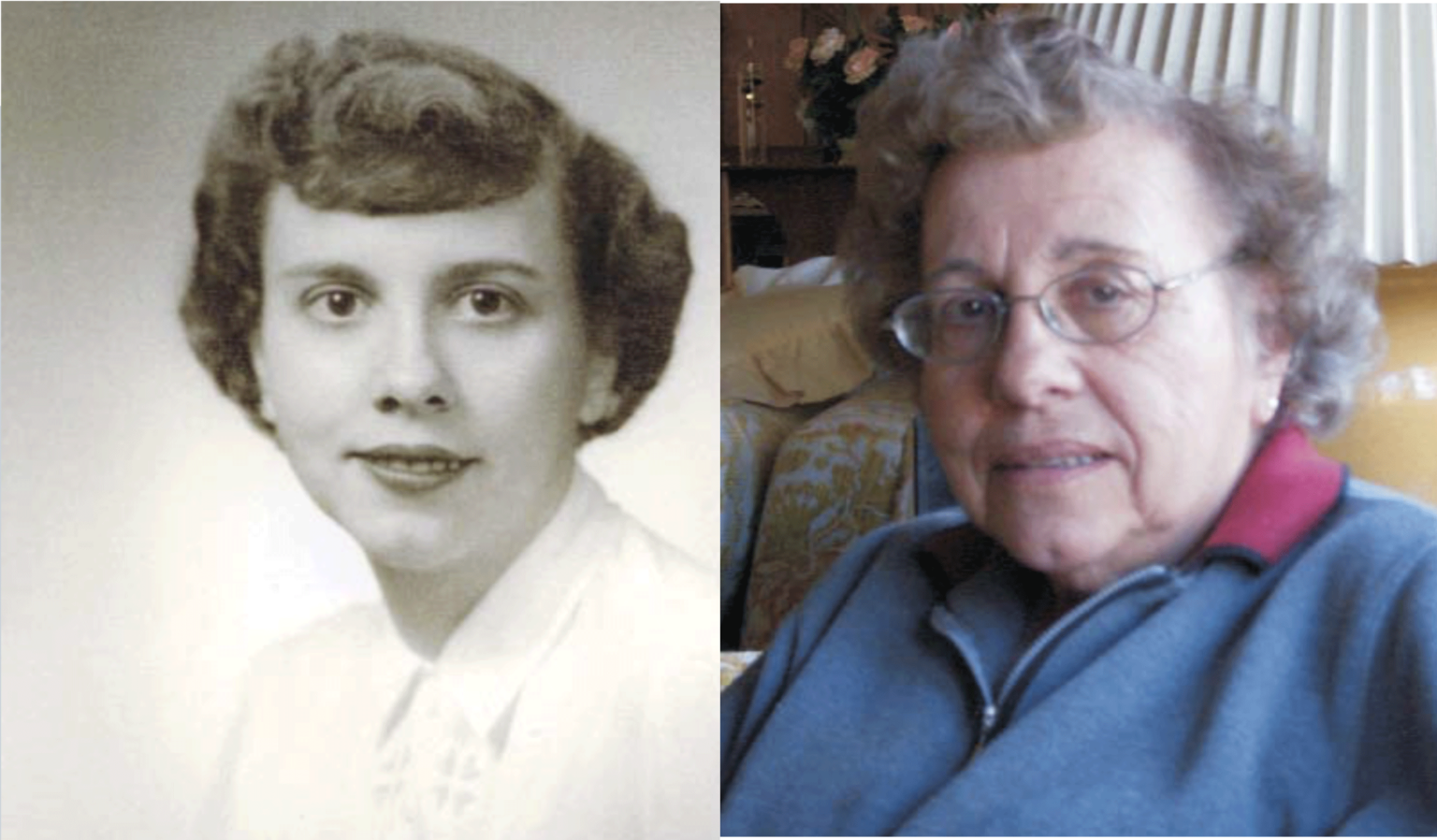

Mary Tsingou: a long awaited recognition for the Greek-American mathematician

The computations for the first-ever numerical experiment were performed by a young woman of Greek descent named Mary Tsingou. After decades of omission, she finally received the well-deserved recognition for her contribution.

The Fermi-Pasta-Ulam (FPU) problem was first conducted in the Los Alamos National Laboratory report “Studies of Nonlinear Problems” [1] back in May 1955. The original paper detailed the methods and results of a mathematical physics simulation run on the MANIAC, the Laboratory’s first electronic computer. Enrico Fermi, John Pasta, and Stanislaw Ulam were the scientists named as authors and were quickly recognized for the remarkable simulation, which came to be called the Fermi-Pasta-Ulam (FPU) problem. In a footnote, the authors wrote, “We thank Miss Mary Tsingou for efficient coding of the problems and for running the computations on the Los Alamos MANIAC machine.”

Programming a 1950s computer was not a trivial task. Nevertheless, her contribution received only this two-line acknowledgment. For nearly 50 years, Mary Tsingou’s contributions to the now-called FPUT (Fermi-Pasta-Ulam-Tsingou) problem were ignored by the scientific community. It was only in 2008 when Thierry Dauxois published [2] additional insights regarding the development of the problem and pushed to be renamed in order to grant her contribution as well. The FPUT problem is of significant importance. It marked not only the beginning of studying nonlinear systems but also the new age of computer simulations of scientific problems, as it represents one of the earliest uses of digital computers in mathematical research.

Human calculators

Mary Tsingou earned her BSc (1951) at the University of Wisconsin and her MSc in Mathematics (1955) at the University of Michigan. In 1951, when she was still an undergraduate student, an instructor informed her that they were looking for women mathematicians at Los Alamos. At the time, women were not encouraged to pursue mathematics. However, the Korean War had created a shortage of American men, so staff positions were also offered to young women. Upon being hired, Tsingou was flatly informed that she and the other young women colleagues would be paid less than men, despite having the same skills and qualifications, because “men were breadwinners and women were just supplementary.”

She was initially assigned to the theoretical division to do hand calculations. Almost all the mathematicians who worked as human calculators at Los Alamos were women, most in their early 20s and just out of college. Using Marchant calculators—early machines that could add, subtract, multiply, and divide—they solved specific problems.

A pioneer computer expert

Tsingou was soon recruited to work as one of the first programmers of the MANIAC (Mathematical Analyzer, Numerical Integrator, and Computer). By then, there was no one that could program it, so when a Los Alamos programmer gave a lecture on programming, it sparked her interest. Mary Tsingou has said in an interview [3] “I was very interested in learning programming, because it was pretty boring sitting there doing addition and subtraction.”

Mary Tsingou along Mary Hunt were the first programmers to start exploratory work on MANIAC. The computer was primarily in use for weapons-related tasks, but the researchers could also use it to study fundamental science for scientific advancement. The MANIAC offered a great opportunity for this, and Pasta and Ulam were among those who quickly spotted it. Once the MANIAC was operational, scientists studied problems that could not be solved with hand calculations but that could be simulated on the computer. Simulations use math to create models of how systems will interact or develop. In simple words, simulations can tell us what would happen if some assumptions were to happen in real life. It is important to mention that Mary Tsingou and John Pasta were the first ones to create graphics on MANIAC.

A leading programmer

Tsingou ended up working on the MANIAC until she temporarily left the Lab in 1954 to get her MSc degree and returned in 1955. She worked on various computers and projects and gained particular recognition for her expertise in an early -back then programming language called Fortran. As an early Fortran expert, Tsingou continued with many more career accomplishments, including editing and manipulating the Poisson Group codes. These codes are still relevant in the 2020s, being used by national laboratories that employ accelerators or electromagnetics. Tsingou was one of the main writers of the code’s manual. Even if the manual has been revised over the years, the sections of the current version are mostly identical to the earlier versions.

Looking back on her career, Tsingou expressed gratitude and fondness for the projects she worked on and highlighted how different the world now is from what scientists back in her time thought it would be. “They thought nuclear energy was going to change the world, but it’s the computers that have changed the world.”

Sources:

[1] E. Fermi, J. Pasta, S. Ulam, Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory report LA-1940 (1955). Published later in E. Segrè, ed., Collected Papers of Enrico Fermi, Vol. 2, U. Chicago Press, Chicago (1965)

[2] Dauxois, Thierry (2008). Fermi, Pasta, Ulam, and a mysterious lady, Physics Today 6 (1): 55–57

[3] We thank Miss Mary Tsingou, Virginia Grant, December 2020