Exploring the invisible: Dr. Ariadni Boziki simulates the molecular world

Chrysovalantou Kalaitzidou

Magazine / Interviews , Science

The career journey of Dr. Marianna Christodoulou began at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, where she undertook a BSc in Biology. She then continued her master and doctoral studies at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, where she focused on Immunology and Human Autoimmune disorders. After completing her PhD, she worked as a post-doctoral researcher at the School of Medicine and Biology of the University of Athens and at the Research Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation at the University of Glasgow. Today, she is based in Cyprus, where she is currently an Assistant Professor of Immunology at the European University Cyprus and the Group leader of the Tumor Immunology and Biomarkers Group of the newly-established Basic & Translational Cancer Research Center (BTCRC). Marianna spoke to Greek Women in STEM about her current research work as well as the milestones of her career path and how these led her to where she is today!

Could you explain in simple words what your research focus is right now?

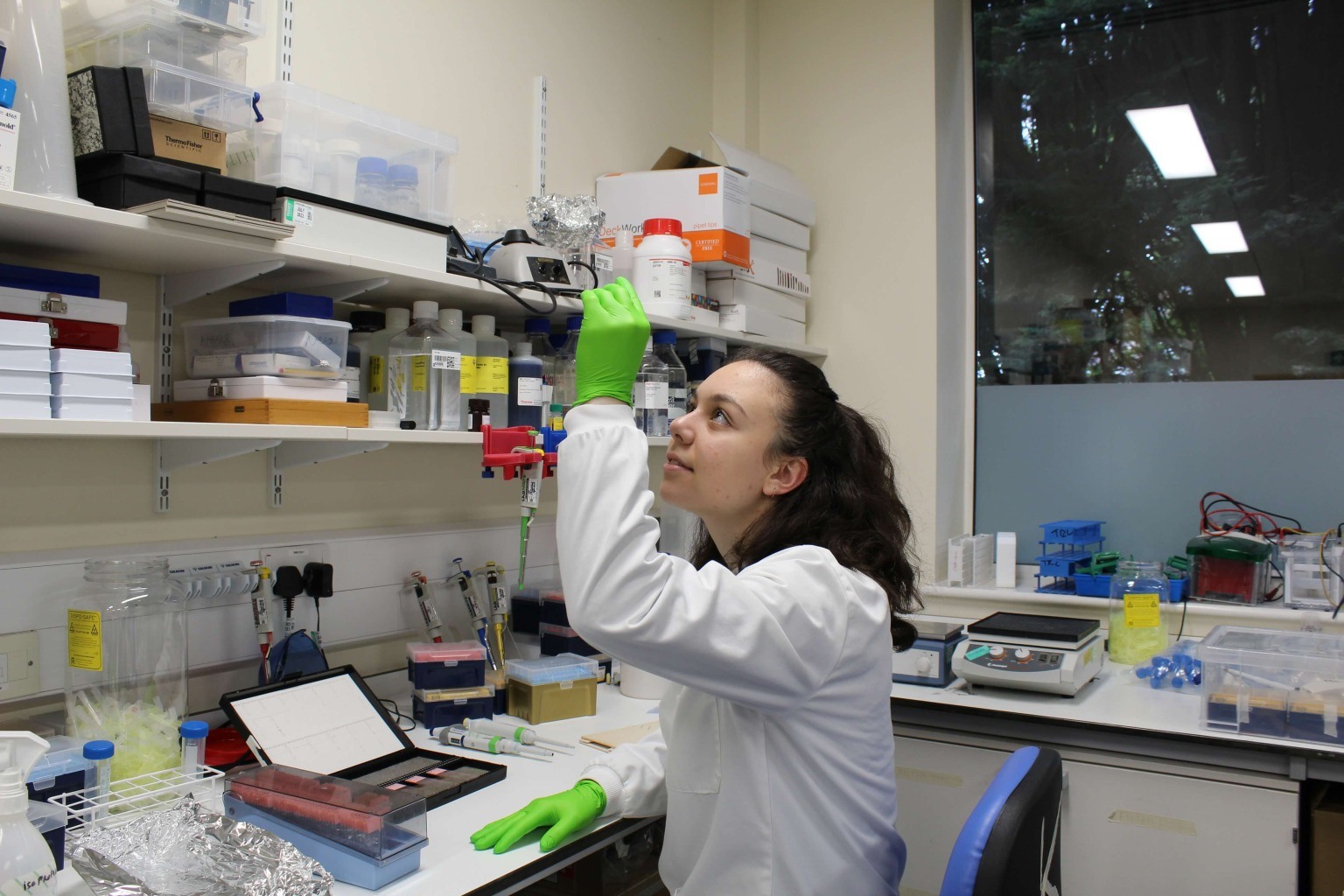

My research lies in the field of Biomedical Translational Sciences, which works towards the application of molecular biology advances in healthcare. The ultimate goal is the development of useful tools for the clinician that will benefit patients and improve their quality of life (from bench-to-bedside approach). My expertise is primarily in the field of immune-mediated conditions. I aim to unravel new components of the immune system (cell populations, genes, and proteins) and comprehend how they impact the development of autoimmune disorders, cancer, and other diseases. To that end, I mainly process human samples (tissue biopsies, peripheral blood, and serum), using cellular and molecular biology techniques, as well as novel “omics” approaches. In contract with the classical methodologies, where a single molecule, or a panel of certain molecules were studied, “omics” technologies give us the opportunity to scan the whole set of genes, other molecules (mRNA, protein molecules etc) and pick-up the “key” ones governing the establishment and perpetuation of a pathological condition.

What is the importance/impact of your research work?

Through my research I primarily aim at a better understanding of the cellular interactions and molecular networks that underly the pathogenesis of certain human immune-mediated disorders; desired outcome is to pin-point molecules or cells that are major players and may serve as possible therapeutic targets and/or potential biomarkers for the diagnosis and monitoring of patients’ response-to-treatment. Introducing such biomarkers in the clinical routine practice would hopefully progress the management of patients towards the improvement of their quality of life and survival rates.

What makes you passionate or inspired about your field of research and workplace in general? What do you enjoy most?

The pathophysiology of human diseases is a field of mystery with hidden solutions. Biomedical research tries to decrypt the signs and unravel the codes to suggest ways to manage diseased conditions. On top of that, our immune system consists of a wonderful network of interactions among different types of immune and other cells, communicating with each other using molecular signals that we have to disclose, understand, and process in order to intervene with therapeutic means. Previous research achievements that are now in use in clinical practice with great success (like cancer immunotherapy) are a great inspiration. However, a lot is missing until we fully comprehend how this cellular universe is governed; trying to gain as much knowledge as we can is a great challenge. Setting a biological question and drawing the path to the answer step-by-step makes me passionate. If this includes training junior scientists and supporting them during their journey to knowledge, is of the utmost pleasure and honor for me.

According to you, what has been your proudest achievement as a scientist so far?

I will never forget when, in 2007, as a PhD student, I was awarded the “Outstanding Abstract Award for exceptional research in Sjögren's syndrome” by the Sjögren’s Syndrome foundation at the 71st Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, in Boston (USA). This taught me that being patient, focused on our goal, doing meticulous work, and aiming at resolving the scientific quiz can give us great results and moral satisfaction. For sure, this award also belongs to my PhD supervisors Associate Professor Efstathia Kapsogeorgou and Professor Haralampos M. Moutsopoulos. Lucky to have them as mentors at the beginning of my career.

Following the routine, the structure, and the plan of different laboratories and departments, interacting with various people, and experiencing everyday life in different countries promoted my academic and personal development.

What has been the most challenging moment you faced during your career? How has this shaped your professionalism and character?

For various personal and professional reasons, I had to work in different academic environments and research laboratories in Greece, Cyprus, and abroad, which, despite the difficulties of the effective adaptation to new workplaces in order to produce research as quickly as possible, was a particular challenge for me. Following the routine, the structure and the plan of different laboratories and departments, interacting with various people, and experiencing everyday life in different countries, promoted my academic and personal development as it broadened my scientific and social horizons, improved my research and interpersonal skills, shot down any bias, made me more mature, productive, receptive in collaborating with people of different temperaments and cultures, and more efficient in communicating with junior and senior colleagues.

Which were the driving forces that pushed you into deciding to pursue an academic career?

As a member of the Academia, I am given the opportunity to pursue high-quality research, participating in various interdisciplinary networks with researchers and academicians from all over the world. At the same time, I am privileged to hold a critical position in delivering knowledge and communicating academic ethos to young people to prepare them to become our future biomedical scientists in various professional posts (academia, industry, and education). The resulting high sense of responsibility is a huge challenge and a strong driving force to keep good standards of quality in my job.

There is an under-representation of women in Senior Faculty positions globally. What are the best ways, based on your opinion, to support the next female leaders in Academia and Research & Development positions?

It is a matter of the general notion that independence, competitiveness, mentorship, etc, the personality characteristics required in leadership roles, are “male” ones. Also, traditionally, women’s priorities are believed to be: raising of children, maintenance of the household, etc, so any other professional obligation, including commitments arisen from a leadership post, stands as an obstacle to what a “woman should be”. Moreover, stereotyping of “male and female jobs” is something done from the first years of education: from early life, when a child starts to imagine their future job, they have already have a “list” of what jobs are accessible to them. For example, a young girl thinks that it is easier and more suitable for her future life to become a teacher than a mechanical engineer. Even when a woman enters academia, in many cases she may face unbalanced distribution of duties: females academics are more prone to be assigned organizational, sometimes even secretarial duties (under the excuse of women being more organized and effective on this), compared to male academics, and this acts at the expense of their academic progress. If she still gains a leadership position, this is considered less than expected and may sound “weird”, regardless of the professional qualifications she may have.

Despite that a lot has been done towards changing these stereotypes, we all, both men and women, have internalized such beliefs and even subconsciously tend to follow them. Thus, it is essential to first start reconsidering our attitudes on this and then give supportive opportunities to women, independent of her personal and family status, to be a member of the scientific community and, if capable act as leaders in Academia or R&D, under equal conditions with a man at the same position.

In your opinion, which changes, if any, are needed within the scientific community to make it more attractive to women in science?

The scientific community per se is already attractive to women in the sciences. It would be even more attractive if it offered equal opportunities (no gender discrimination, no homosocietal groups) and avoided the reproduction and attachment to stereotypical and binary gender roles. There are already some regulations aiming at abolishing this bias (like the predefined male-to-female ratio in research projects, etc), however establishment of agencies/institutions for monitoring gender equality issues would reassure the application of these regulations.

In any case, the most critical point, to my opinion, is reconsidering our attitude on the subject, and it is auspicious that things are slowly changing in newer generations. Nevertheless, much remains to be done, especially at an early age and in primary education, where gender and role discrimination are now being promoted, so that mature adults, in any professional and social environment, behave and act unbiased towards a gender-equality direction, without the need for additional rules and surveillance.

If you had the option to give advice to young female scientists, what would that be?

My advice would be that Female scientists should not be discouraged and must follow what they themselves, not their families or society, believe they were born to do and set their own priorities for their lives. Science is for everyone who loves and serves it.

Find out more about Dr. Christodoulou on her research group page or follow her on LinkedIn.

Chrysovalantou Kalaitzidou

Thaleia-Dimitra Doudali

Danai Korre